This is an opinion piece by Paul Jan Jacobs, founder of EVBoosters Executive Search (2018). He has been active in the electric mobility and EV-charging industry since 2010, advising companies across Europe on leadership, strategy, and the transition toward electrified transport.

Stepping back when clarity, conviction and pace are crucial

When the European Commission announced on 16 December 2025 that it intends to weaken key elements of its automotive package, including reducing the 2035 CO₂ reduction target from 100 to 90 per cent, I had to read the news twice. This was Europe stepping back at precisely the moment when clarity, conviction and pace are crucial. The new target effectively allows eleven grams of CO₂ per kilometre instead of zero, meaning combustion engines may remain in the market far longer than anticipated. The Commission even expects that up to 29 per cent of new cars sold after 2035 could still contain a combustion engine.

And this hits me even harder because I have spent fifteen years working in electric mobility, watching Europe drift and hesitate in its electrification policy. The direction has always been obvious, but the speed, consistency and strategic courage have never matched the urgency. This latest decision reinforces a pattern of hesitation that Europe can no longer afford.

European EV Market is advancing strongly

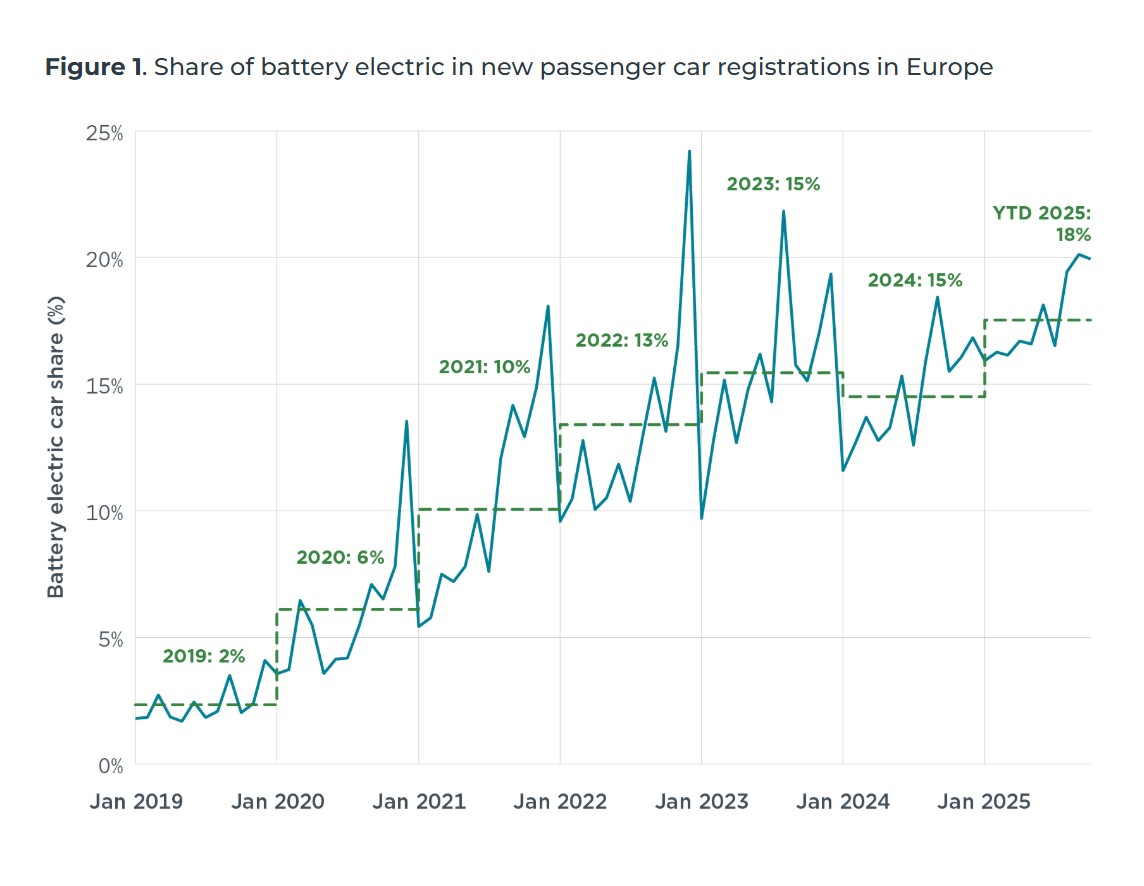

Despite the policy uncertainty at the EU level, the market tells a different story: electrification is advancing strongly on the ground. According to the latest European Market Monitor for Cars and Vans, battery electric vehicles (BEVs) accounted for 20 percent of all new passenger car registrations in October 2025, holding steady at this share compared with previous months and marking continued progress toward cleaner mobility. Year-to-date BEV market share has risen to 18 percent, up 4 percentage points from the same period in 2024.

Importantly, this growth is not limited to premium models. European OEMs such as Volkswagen and Renault have reported double-digit increases in EV sales thanks to the introduction of more affordable electric models, with studies showing these brands growing significantly year-on-year — in some cases by around 60 percent and even 80 percent respectively, driven by rising consumer demand for competitively priced BEVs.

Pyrrhic victory for supporters of the combustion engine

At first glance, this appears to be a political win for those determined to “keep the combustion engine alive.” Plug-in hybrids, range extenders, mild hybrids and even pure combustion engines may remain technically allowed. But this victory comes with conditions that are likely to be prohibitive. Every gram of CO₂ emitted after 2035 must be offset through a new credit system. Manufacturers will have to compensate these emissions using green steel, biofuels or the still highly speculative e-fuels. The availability and affordability of such materials by 2035 is far from guaranteed. In reality, combustion engines may remain legal, but economically inaccessible for most customers. Symbolically alive, but practically unworkable.

Europe hesitates while China executes

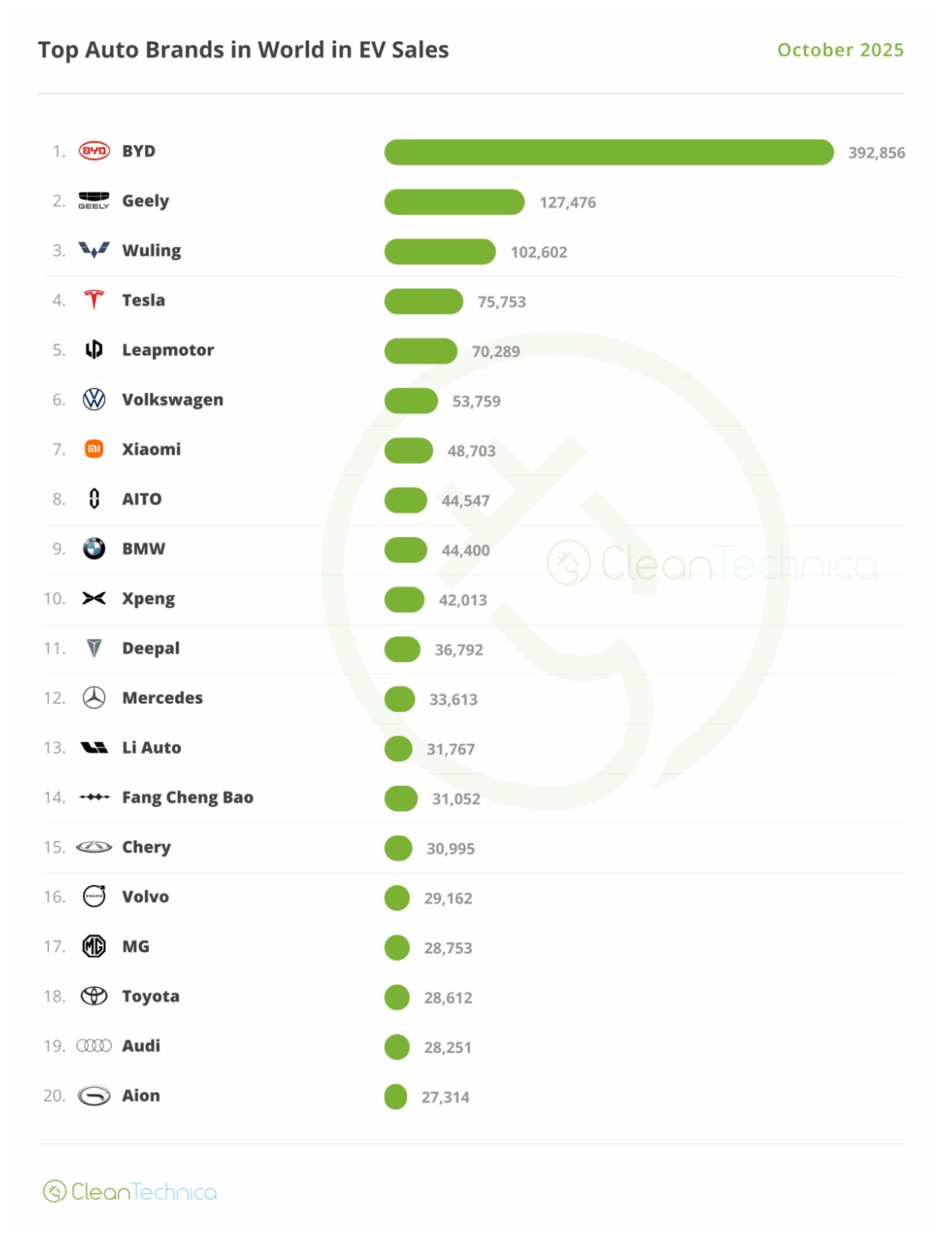

The contrast in mindset could not be clearer. While Europe negotiates exceptions and timelines, China continues to scale EV manufacturing, battery capacity and software with remarkable discipline. Electrification in China is not a political football. It is an industrial mission. Each year, the gap widens. Europe hesitates, China executes.

Since 2010, the trends have been unmistakable: falling battery prices, rapidly expanding charging infrastructure, software becoming central to vehicle architecture, and bold investment from Asian competitors. Yet many European incumbents behaved as though these developments were optional. Strategies were diluted, timelines extended, and legacy models protected. Instead of preparing for the inevitable, many hoped the disruption would simply fade.

A deer in the headlights is not a strategy

Europe saw the transition approaching but failed to act decisively. The hesitation was visible everywhere. And now that the consequences can no longer be ignored, industry leaders have turned not to leadership, but to lobbying. Weakening the CO₂ framework dilutes investment signals across the entire value chain, from battery factories to software platforms to charging infrastructure. It creates uncertainty precisely when Europe needs alignment and long-term confidence.

The Dragdi Report wake-up call

This is not merely a climate issue. It is a strategic industrial issue that will determine Europe’s position in the global automotive landscape for the next 25 years. Weak regulatory signals slow investment, cause scale-ups to lose momentum and give global competitors a clearer and faster path forward. Chinese OEMs benefit from tight alignment between regulation, capital and industrial strategy. Europe, by contrast, risks drifting into a fragmented and reactive posture. And this is precisely the core message of the Draghi Report. The report warned that Europe’s competitiveness crisis is structural, that the continent lacks speed, coherence and long-term industrial vision, and that hesitation is the single greatest threat to Europe’s economic future. All EU member states agreed with these conclusions, recognizing the urgency and the need for decisive action.

Yet here we are, only months later, falling back into the same old patterns. Instead of building clarity, we reintroduce ambiguity. Instead of accelerating investment, we weaken the very signals required to mobilise it. Instead of acting with unity and ambition, we retreat to short-term national comfort zones.

Europe knows what is required. The tragedy is that we still fail to act accordingly.

The victim narrative is tempting, but it weakens Europe further

Yes, China subsidies heavily. Yes, protectionism exists. Yes, intellectual property has at times been acquired through questionable means. But none of these external factors explain Europe’s slow execution, fragmented markets, or years of underinvestment in core capabilities. Blaming others may feel comforting, but it does nothing to accelerate Europe’s transition. Responsibility cannot be outsourced.

Leadership requires looking in the mirror

What we see in Brussels now is not leadership under pressure. It is avoidance. It is choosing political maneuvering over product excellence, and delay over decisive action. Meanwhile, customers, both consumers and fleets, choose the products that perform best. Nationality is irrelevant. Performance, reliability and total cost of ownership are not.

Europe still possesses extraordinary strengths: deep engineering capability, strong brands, world-class research institutions and the scale of a unified market. But strengths without urgency quickly turn into complacency, and complacency is fatal in a transition defined by speed.

Leadership is not asking for more time after ignoring the clock for a decade. Leadership is acting when it is uncomfortable, especially when the stakes are high. And right now, Europe needs leadership far more than lobbying.